To coincide with the release of ‘Gladiator 2’, we wanted to highlight Stéphane Bucher's work with director Ridley Scott. This collaboration began in 2020, for ‘The Last Duel’, a year in which nothing went according to plan. Stéphane Bucher wasn't even supposed to be working on this film! Since then, Ridley Scott has been working on one project after another, and Stéphane Bucher has become his indispensable ‘French Sound Man’.

DPA: Hi Stephane, can you tell us a bit about your career?

SB: I have a classic background with a BTS in audiovisual, specializing in sound. Then I started working as a boom operator for 7 years on TV films and series. In 2010, after becoming a sound engineer, I had the opportunity to work with EuropaCorp, Luc Besson's production company, collaborating on 11 films, including three with Luc. What's interesting here is EuropaCorp's working process in film production. These films are almost entirely aimed at a specific market, which means that working methods, film construction and shooting techniques are largely inspired by Anglo-Saxon practices. In particular, this involves the use of considerable resources, multi-camera shoots and a different approach to filming than we are used to.

In France, we follow a more traditional method, a craftsman's approach where the teams know each other well. There's nothing pejorative to be said about craftsmanship, because it allows incredible things to be achieved, but the way it works is different. We often have rehearsals and discussions before shooting. Today's Anglo-Saxon methods, which were also used at EuropaCorp, are more ‘frontal’. We use four cameras, the director sets up the actors, then the cameras are positioned, and the actors enter the scene. We shot immediately, with no prior rehearsal. Another notable difference is the size of the teams and how they operate. The scale is completely different.

1. The meeting during The Last Duel

DPA: Your meeting with Ridley Scott must have been a significant moment, I imagine? How does a French sound engineer end up working with one of the world's greatest filmmakers?

SB: It's an interesting and rather funny story. It all started when a local French production hosting Ridley Scott for the filming of ‘The Last Duel’ was looking for a sound engineer. Ridley Scott's production wanted to cast a sound engineer. At the time, in December 2019, I had just finished making ‘The Eddy’ for Netflix, after working non-stop for a year without taking any holidays. I had planned to take a break at that point, so I went to the casting relaxed, telling myself that if I wasn't selected, it wouldn't matter because I was exhausted and needed a rest.

They explained to me that all I had to do was send in a CV, which I did, and three or four weeks later they called me back to tell me that I was on the short list, that there were only three sound engineers left, and that Ridley Scott now wanted letters of recommendation from three re-recording engineers. It made sense, because they are the ones who can best objectively assess the work of the sound engineer. Thanks to my experience at EuropaCorp, I met several of these mixers, including some big names in Los Angeles and London. I was easily able to get 2 letters of recommendation from Tom Johnson (12 Oscar nominations and 2 wins) and Dean Humphreys. But I was short of one, and having recently finished ‘The Eddy’, I thought the recommendation of the director, Damien Chazelle, would be relevant, as he is very well known in the film industry and passionate about sound and music. So, I wrote to Damien, and he said he'd be happy to recommend me.

DPA: What was your first meeting with Ridley Scott like?

SB: The story is quite amusing and stressful at the same time! A few days before shooting began, I approached the French production to ask them to do some location scouting, to visit the shooting locations to check the sets and anticipate any problems. The response was quite surprising: ‘Oh no, the English production doesn't think it's necessary for you to do location scouting’. I replied that this was a bit strange, especially for ‘The Last Duel’, but I was reassured that I could come the day before or two days before shooting, without any problem. I did, however, plan to prepare well in advance, being in Paris, whereas the shoot was scheduled in the middle of France, with an airport two hours away.

A week before the shoot, everything was ready, and I was still at the equipment hire company when I received a call from the production team announcing a day of pre-shooting... What is a pre-shoot? It's a Ridley Scott specialty: if we start the first day of principal photography on the Monday, the Friday before he adds another day of shooting. It's a sort of test day, to get the team into the swing of things and check that everything's running smoothly... It was Tuesday of that week, 3 days before the pre-shoot, and I still hadn't arrived. On Tuesday morning, the production team called me and told me that the American executive producer wanted to know where I was. They couldn't understand why I hadn't done any location scouting and why I wasn't already there! I reminded the production team that they had told me that my participation in the location scouting was not necessary. The producer then asked me: ‘Can you catch the next flight here in two hours, it's important! Fortunately, I'd already packed all my stuff, and everything was ready. I said ‘OK’, got on my scooter, went home, got my suitcase all packed [laughs], hailed a taxi, rushed to the airport and that was the start of a crazy race.

Once I got there, I quickly realized the phenomenal scale of the project. Everything was there, the crews, the four cameras, the special effects, the horses, and I started to get really stressed [lol]. When I arrived, I met Ridley with Ray, his first assistant. I greeted them by saying ‘hello’, and they asked me ‘ah, who are you? I reply ‘Well, I'm the production sound engineer’ and they say ‘ah, you're the sound guy, ah very good, welcome, glad you're here’!

My team, Jérôme Rabu (1st Boom Operator), Claire Bernengo (2nd Boom Operator) and Agathe Michaud (Trainee), arrived 24 hours later, 2 days before shooting was due to start. After spending the last 48 hours trying to get completely ready, the day of the pre-shoot arrived.

DPA: Incredible! Did this ‘pre-shoot’ day go well?

SB: It was maximum stress. As soon as I arrived on set, I bumped into Ridley's script girl, Annie Penn, who came up to me in a determined way and said: ‘Ridley hates post-synchronization, and there will be wide shot cameras and tight shot cameras, smoke machines, and lots of other things. Do what you want, get on with it, but if you have a problem, go and talk to him about it. I know sound engineers are always worried about going to him, but really, you've got to go and tell him, because if you don't, it's too late... Sorry to be so blunt. Good luck, take care and have a good day.’ And off she went...

Finally, to finish the story of this meeting, which was a bit long, you should know that every evening Ridley went to watch the footage we'd shot the night before in a well-equipped room in the hotel with a big screen and good speakers. After 2 weeks of shooting, he came up to me and said, ‘You're the sound engineer, aren't you? I replied: ‘Yes, yes, that's me. And he says: ‘Listen, I just wanted to thank you for your work. I'm very happy with the sound, that's what I'm looking for, that's how I see things. So, I'd like to thank you for being with us. I'm very happy, I tell you’. And he left. I told myself that the gamble had paid off. A few weeks later, it was the end of shooting and Ridley said to me: ‘You're going to continue working with me, we're going to do “House of Gucci” in Rome!

2. House of Gucci

DPA: Following this first experience on "The Last Duel," did you change the way you worked on the next film "House of Gucci"?

SB: Yes, absolutely. Not only in the way I collaborate with my team, but also in terms of technical resources. As far as my team was concerned, it was necessary to review the organization. Giving different responsibilities to my collaborators became crucial. For example, the microphone positioned over the actors became extremely important. We had to review our approach with the actors, the explanations and the use of new props. It very quickly became necessary to create a post of sound assistant dedicated to this task. The choice of DPA microphones was then a certainty, so I opted for 4060 miniatures and a few 6060 subminiatures as well. For some scenes, this was really the main microphone for the sound recording, because using several cameras at the same time meant that I couldn't get the boom close enough without being visible in the shot.

In terms of technical resources, a lot of things had to be rethought, particularly the geography of the work spaces. Usually, the sound engineer is close to the set, but here, with multiple cameras filming in all directions, he had to keep his distance. This posed a problem in terms of the limitations of Wireless microphones. The idea was to find a way of positioning my workstation next to Ridley Scott's space, i.e., between 50 and 100 meters from the set. It was on ‘House of Gucci’ that I first used an Wireless Audio Limited rack directly on the set with a DANTE connection to my sound console.

3. Napoléon

DPA: The next film, "Napoleon," must also have been a technical challenge in terms of production size, right?

SB: In fact, there must have been 300 of us technicians working on gigantic sets. Ridley used up to 11 cameras for certain scenes. Once I'd been able to analyze the script, once I'd had a glimpse of what the directions were, what the challenges were, I made my own decisions in terms of choice of equipment and human resources. Then I inform the production team of my needs, and I'm lucky enough to have producers who listen to me perfectly. For example, if I need seven assistants, they listen to my explanations and give me my seven assistants. The same goes for the technical side. In return, the result has to be up to scratch.

‘Napoleon’ was a very important film in terms of research into timbres, voices and the positioning of the HF microphones in the costumes. It's interesting to note that the choice of microphones and placement also depends very much on the constraints of the sets and the actors' movements. In intimate scenes, the boom is used more intensively to create a close, immersive atmosphere. Conversely, in more complex situations, such as combat scenes, innovative strategies are implemented, such as the use of soldiers' blankets to hide the DPA microphones.

This preparatory work was done in advance, over a period of almost 15 days. It was quite intensive, particularly with my 1st boom operator Josselin Panchout and Stéphane Maléfant, who were responsible for assessing the costumes beforehand, placing the microphones, listening to the results, and sending me the files when I was busy with other tasks. This allowed us to check that everything was in order before we even started shooting. Careful preparation of microphones, costume tests and close collaboration with the film crew are key elements in ensuring quality sound in sometimes difficult conditions. Once again, this demonstrated the importance of the coordination and preparation process with the crews.

DPA: How did you manage to achieve this sound result on the battlefield?

SB: I wanted to adopt a unique perspective. The first thing I wanted to do was to ensure that the audience heard the full extent of the sound of the battles, to give them a sense of listening to the whole thing. To achieve this, the first idea was to have one person dedicated to capturing the ambience, equipped with a small autonomous recorder, the MixPre from Sound Devices, and a boom with an LCR microphone.

This person was independent, which was necessary given the scale of the sets. It was impossible to run 100 or 200 meters of cable to connect the signal from the microphones to my recorder, so mobility was essential. So, this person would capture the atmosphere from an extremely wide angle, to get an initial listening perspective. He would often position the boom as high as possible to get as wide a view as possible. The second perspective was to get closer to the battle. To do this, I used my four boom operators. These poles were distributed according to the movement of the cameras.

I had eight cameras, sometimes as many as eleven during the battles. Naturally, some of them were positioned to get a very wide shot. However, there were cameras inside the battle itself, and the camera operators were dressed in costumes, so as not to be seen, and moved around inside to capture the moments of close-up combat, while my assistants were also dressed as soldiers.

Finally, to get even closer, the strategy was to equip the stuntmen. The idea was to get very close to the battle itself and capture the voices to get a kind of immersive sound. I didn't want to place a microphone directly in the stuntmens' clothes because they were fighting, and I would only have been able to get sounds of the material rubbing against the costume. So, we decided to use each soldier's rucksack.

On top of the bag was a blanket, which was the ideal place to place a DPA 6061 microphone. The aim was not to capture the person themselves, but the two square meters around them. 10 stuntmen were equipped, and these stuntmen were dispersed in the battle. Obviously, there was no question of providing Wireless transmission, so the Audio Limited A10 transmitters were set to recording mode with a time code. Then, at the end of the day, I collected the 10 SD cards to transmit the sounds to post-production. The hardest part wasn't putting the microphone with the A10 transmitter into these bags, it was finding them at the end of the day! Luckily, a photo was taken of each of the stuntmen to make it easier to find them among the 500 extras! As an anecdote, one day we spent literally three hours looking for the person we'd equipped, unable to find out where he was... We had to check a mountain of rucksacks piled up to two meters high to find our microphone, but nothing... The next day, we finally found it, but on the battlefield!

4. Gladiator 2

DPA: At last, we come to ‘Gladiator 2’, which is currently enjoying an exceptional worldwide release! The first question I'd like to ask you is this: how did you feel about managing the sound for such an iconic film as ‘Gladiator’?

SB: Very badly! (laughs) In fact, this film was and will certainly remain the most important in terms of budget, size and number of technicians of all my career. And above all, Ridley had decided to use 8 cameras absolutely all the time. And up to 12 for the battles. We had to rethink the organization of the team and the technical resources. So, it was a very big challenge indeed.

DPA: What were the main technical changes?

SB: It was clear that shooting ‘Gladiator 2’ was going to be even more complicated than shooting ‘Napoleon’. So, I wanted to resolve certain technical limitations in relation to my usual configuration. First of all, the use of Dante with Ethernet cables imposed a distance limitation of 75 meters maximum (100 meters in practice). As the main set is more than 300 meters from one end to the other, I decided to use fiber.

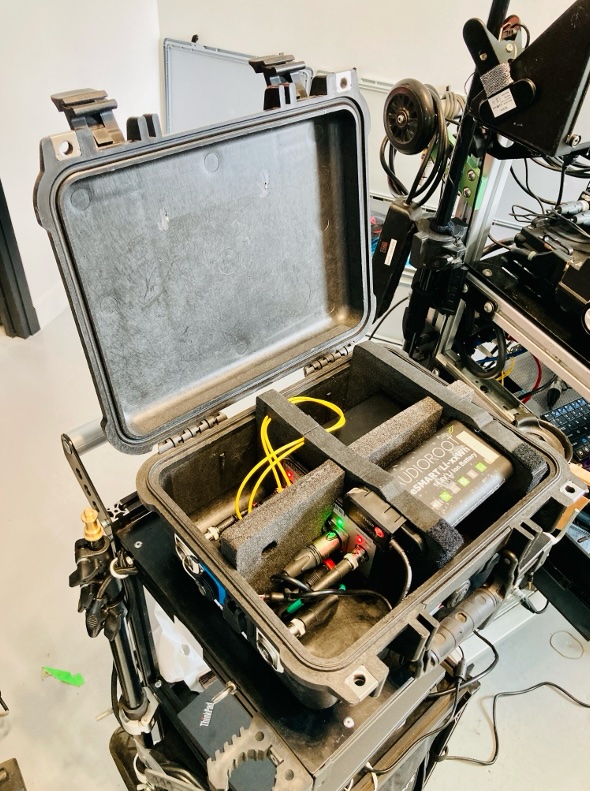

The main cart (with the Cantar recorder) and the « on set cart » called « Maximus »

The main cart (with the Cantar recorder) and the « on set cart » called « Maximus » I started by creating a second rig on wheels, which we called ‘Maximus’ in honor of the main character in the first ‘Gladiator’ (Russell Crow). ‘Maximus' consisted of the receivers for the wireless mics, the mics for the various booms and a back-up recorder. ‘Maximus was placed on the set close to the actors, while the main trailer and I were sometimes positioned 300 meters away. In addition, the fact that a lot of different information was exchanged between the machines meant that we had to use 2 CISCO switches connected by trunk to be able to receive all the data on a first IP layer and to be able to control all the equipment remotely.

To facilitate the installation of this additional extension, a ‘Peli case’ box containing all the components was made with the help of Fréquence. The unit included Broady Solution's RF over Fiber system, a power supply using an Audioroot battery system and a set of connectors located directly on the outside of the Peli case.

To give you an example of the deployment of this solution, there is a sequence in the film that clearly illustrates the need for this type of tool: the moment when General Acacius (Pedro Pascal) returns victorious from the battle of Numidia. Well, this sequence was filmed in a single shot with 8 cameras positioned along the entire 300-meter route.

We had to install the ‘Maximus’ mobile with the first pair of antennae halfway along the route, then the RF over Fiber system with the second pair of antennae close to the finish point. Thanks to the Wisycom MRK16 reception rack, I was able to control the different zones and get a good reception signal from the wireless microphones.

Another major challenge was the colossal work on the costumes in collaboration with Janty Yates and her team. We had to find the best microphone positions on these magnificent period costumes because for some of the sequences, the DPA microphone became the main and only audio source for the actor's voice.

For lead actor Paul Mescal (Lucius), for example, one of the challenges was to find a solution for the placement of the microphone and transmitter for the famous armor of Maximus (Russel Crowe), from the first Gladiator, which Paul had to wear for the last part of the film. Paul wore this armor for fights but also for dialogue scenes.

The choice of microphone was the first issue. As far as the fighting was concerned, it was obvious that the use of a microphone with a high dynamic range was essential in order to capture the cries and sounds of effort without distortion. But the microphone also had to be protected from the wind while being sufficiently ventilated and not under a thick layer of leather. The solution was found with HOD costumes armorer master Giampaolo Grassi, who was in charge of the leather armoring on the film, in order to obtain the space needed to position the microphone.

A DPA 6061 was chosen with URSA Plush Sleeves wind protection. This space was just behind the shape of the silver horse. For the record, during Lucius' speech to the army at the end of the film, it was this microphone and only this microphone that captured Paul Mescal's voice. With more than 8 cameras positioned, it was impossible to place the boom microphone close enough to Paul to obtain the sound of his voice at a sufficiently high volume for this sequence.

DPA 6061 microphones

This kind of work was conducted on almost all the costumes. For Denzel Washington, who played Macrinus, it was the numerous gold necklaces he wore...

Denzel kept asking the costume departments: ‘Macrinus needs more gold... give me more gold !!!’. And we were going along behind to fix the elements with transparent sticky pastes in order to attenuate the noise of the metal... It was epic! And so was the film...

Denzel Washighton as Macrinus

Denzel Washighton as Macrinus

DPA: Any last words?

SB: I just wanted to thank the teams at DPA for their support over the last few years and congratulate them once again on the quality of their microphones. It's always a pleasure to talk to them and I hope to be able to share new adventures again soon!

Follow Stephane Bucher on Instagram: sbsoundmixer